Perfectionism vs Perfection

Reflection for the 2nd Sunday in Ordinary Time

https://www.lifeissues.net/writers/mcm/mcm_440perfectionismvsperfection.html

https://wherepeteris.com/perfectionism-vs-perfection/

Deacon Douglas McManaman

It is too small a thing that you should be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to restore the survivors of Israel; I will give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth.

This is an interesting line from the first reading: “It is too small a thing that you should be my servant…” Is it too small a thing that Israel should be “my servant”? Or is it too small a thing “to raise up the tribes of Jacob”? Perhaps both. I say this because our God intends to raise us up to be his equals, so to speak, and since friendship is based on a kind of equality, God intends to raise us up to the level of friendship. We read in the gospel of John: “I no longer call you servants, because a servant does not know what his master is doing. I have called you friends, because I have told you everything I have heard from my Father” (Jn 15, 15).

What raises us up to that level of equality (friendship) is divine grace, which is a sharing in the divine life. It was St. Athanasius who said that “God became man in order that man might become God”. He became man so that divine grace may run through the veins of humanity, as it were, so that humanity may become the temple of the Holy Spirit, the dwelling place of the Lord. Grace is that which “makes holy”. But holiness, unfortunately, is often confused with sanctimony, and sanctimony tends to get mixed in with perfectionism, which in turn is usually a means of shaming others–children in particular. But holiness is not perfectionism. Holiness is love; holiness is charity.

We read: “I will give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (Is 49, 6). But how can we become a light to the nations? God is Light, not us. We can be a light only by reflecting light, as a mirror does. But a mirror must be clean in order to receive the divine light and reflect it. However, in order to see the dirt and grime to be cleaned, one needs light, because one can’t see anything in the dark. But the dirt and grime prevent the mirror from receiving the light that is to be reflected, and so only the light can clean the mirror. In other words, we cannot clean ourselves in order to make ourselves receptacles of the divine light. If we take it upon ourselves to clean the mirror of our souls, we only end up becoming perfectionists, and perfectionism is not holiness.

It sometimes happens that a person who has a late conversion in life will go to religious extremes. I believe that in such cases, since they will have spent a good part of their lives not at all concerned with the will and worship of God, they will have acquired certain vices along the way, such as a disposition to anger, or envy, the need to be “one up” on others, or the need to control others, or the need to be approved by authority figures, etc. The problem is that bad habits are hard to break and virtues take time to acquire, so what can happen is that these late converts can bring those habits into their new “religious life”, and this can cause a person to look for ways to continue in these behaviors, but under a religious guise. This is where sanctimony becomes confused with holiness, and there is a danger of becoming finger wagging perfectionists who will often find ways to stand out from others.

I was part of a discussion recently in which a number of us were wondering whether or not everything Christ did was done perfectly. We all agreed that Jesus did not sin, but one person insisted that when Jesus the carpenter was sawing wood, for example, he would have made mistakes, perhaps cut the wood too short, or perhaps the table he made was not perfect in every way. Others took issue with this, insisting that Jesus was God, so he would have done everything perfectly. But we have to ask ourselves: Wasn’t he like us in all things but sin (Heb 4, 15)? If Jesus were to play baseball, would he have hit a home run every time or struck out every batter? Or, if he were in the Olympics, would he have won a gold medal in every event? Consider when Mary found Jesus in the temple: “Son, why have you done this to us? Your father and I have been looking for you with great anxiety.” Jesus was a 12-year-old boy, and like a typical adolescent male was almost exclusively focused on one thing. Our purview starts out very narrow but gradually widens as we grow in experience and we begin to consider things that we would not have considered in your youth. To deny Jesus that development is completely unwarranted. Life is a learning process, and to be part of that learning process is to experience normal human imperfection–not moral imperfection, not folly, but the need for growth. I believe we can make the case that he experienced the imperfection that belongs to material existence, and because he is the God-man, he sanctified human imperfection. Hence, there is indeed a kind of beauty in imperfection (Conrad Hall).

The only thing he cannot sanctify is sin. Imperfection, on the other hand, is nothing to be ashamed of. In fact, there would be far less misery in this world if more people would come to accept their own limitations and imperfections and give up the need to achieve perfection.

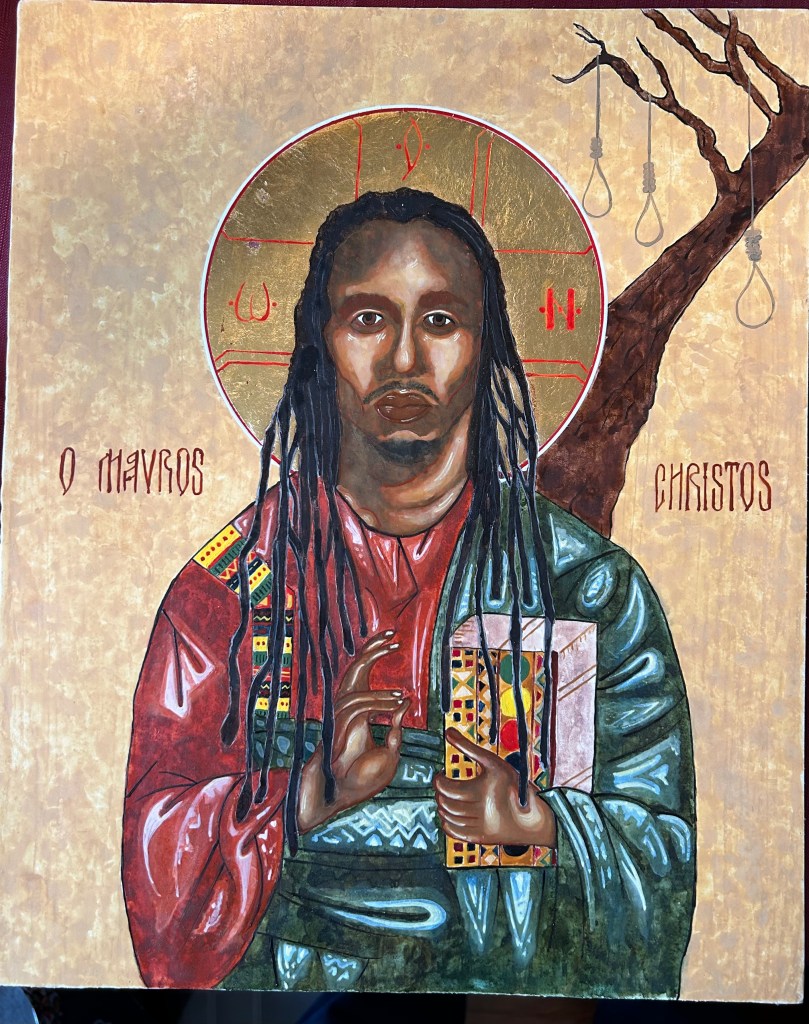

Jesus did say “Be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect”. What he was referring to, according to St. Augustine, was perfect charity. We see this from the context: “Love your enemies, pray for those who persecute you, for God makes his sun shine on the wicked and the good” etc. Holiness is love, and God’s love was made visible in the Person of Christ, who descended, who emptied himself and took the form of a slave, and entered into our death in order to inject it with his divine life. And so, we become like him by descending, not by ascending. The way to ascend to God is to descend with him and love what he loved, and he had table fellowship with social rejects. Christ was not a temple priest. He was out in the world, mixing it up with the sick, the suffering, the lost and forsaken.

The spiritual life is a gradual letting go of all that blocks the divine light; it is about allowing the divine light to burn within us all disordered love of self, which is what keeps us from genuinely loving others. God is a consuming fire (Heb 12, 29), a refiner’s fire (Mal 3, 2). A blacksmith puts the iron in the fire to soften it, to make it more malleable, and then he hammers it into the shape he envisions for it. Outside of that fire, the iron remains hard, rigid, and unbending, but when placed in the fire, it begins to radiate with the color of the flame.

We do have a tendency to regard suffering, trials, difficulties as anomalies, as signs that something is terribly wrong, that we are in some way being punished by God. This is a serious misconception. In this gospel, John says: “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world”. This is Christ’s fundamental identity, the Lamb of God who has come into the world to be sacrificed. The most significant moment in the New Testament took place in the Garden of Gethsemane: “Lord, let this cup pass me by; but not my will, but your will be done”. He felt the size and weight of this obstacle, but these words were his victory, and we get to share in that victory all throughout our lives each time we are confronted with difficult and fearful choices. Our task is to allow ourselves to be molded by his hands, to allow him to make us like himself.

But what is he like? We just have to look at a crucifix. That’s what he is like. It is rather easy to live a kind of religious life that amounts to a continuous evasion of the cross. We see this, for example, in those who, while they love liturgy, vestments, incense and candles, processions and liturgical drama, will demean others, look down upon them, make their authority felt and use religion to oppress others, especially women. The Church is a strange mixture of the divine and the human, holiness and sin, a mystery that can only really be understood from the inside. We see the results of this tragic mixture all throughout the history of the Church, alongside those who are genuinely saintly, like Don Bosco who devoted his life to poor youth on the streets during the time of the Industrial Revolution, or Vincent de Paul, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, Benedict Joseph Labre, Padre Pio, John Neumann who dedicated his life to the immigrants of Philadelphia, learning 8 languages in order to hear their confessions and who died on the street at 48 years of age while running some errands. And when I look back at my own life, I have encountered both those who have been a negative influence, who have done harm and have driven people away from the Church by their misogyny, legalism, and abuse of authority and who made their priesthood principally about them, alongside great men and women who had a tremendous influence on me, such as a very humble Salesian priest, an unpretentious and joyful diocesan priest from Washington D.C., who was violently murdered during a robbery, and countless women who were hidden vessels of divine patience, carriers of the divine light and love.