The Consecration of Married Life and the Authority of Christ

https://www.lifeissues.net/writers/mcm/mcm_403homily1.29.2024ordinarytime4.html

Deacon Doug McManaman

It was very difficult to discern an underlying thread in the readings for the 4th Sunday in Ordinary Time, so I will settle upon making just two points. The first point bears upon the second reading taken from Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, chapter 7: “Brothers and sisters: I should like you to be free of anxieties. An unmarried man is anxious about the things of the Lord, how he may please the Lord. But a married man is anxious about the things of the world, how he may please his wife, and he is divided. An unmarried woman or a virgin is anxious about the things of the Lord, so that she may be holy in both body and spirit. A married woman, on the other hand, is anxious about the things of the world, how she may please her husband. I am telling you this for your own benefit, not to impose a restraint upon you, but for the sake of propriety and adherence to the Lord without distraction” (32-35). Because it is a small portion of the entire chapter, taken out of its larger context, it is very easy to misinterpret; one can easily come away with the impression that the celibate life or the consecrated life is genuinely religious, while the married state is not. Such an interpretation, however, would be contrary to Paul’s overall teaching on marriage, not to mention all the developments in the theology of marriage over the centuries, especially the more recent theology of the body of Pope John Paul II. In the larger context of this chapter, we see that Paul believes we are in the last period of salvation history. He refers to his own time as a time of distress, which in apocalyptic literature, is said to precede the time of the Second Coming of Christ. Paul writes: “So this is what I think best because of the present distress: that it is a good thing for a person to remain as he is. Are you bound to a wife? Do not seek a separation. Are you free of a wife? Then do not look for a wife…. I tell you, brothers, the time is running out” (26-27; 29). What he says about those who are married and those who are not must be read in this context, otherwise we come away with the impression that marriage has nothing to do with serving the Lord. And of course, that would contradict what Paul teaches in his letter to the Ephesians, where he speaks of marriage as a sign of the love that Christ has for his Bride, the Church.

Christ’s love for his Bride is a conjugal love, and the love of a baptized husband for his baptized wife is that very same love, and vice versa. This is what we try to get across to couples in Marriage Prep classes, namely, that marriage is just as religious a vocation as is the priesthood and consecrated life. It hasn’t always been understood that way, unfortunately, due to a kind of clericalism that Pope Francis has spoken out against so often in his papacy. But marriage is a sacrament, a sacred sign that contains what it signifies, and it signifies the paschal mystery. For just as God called Abraham to leave the land of Ur and go to the land that He will lead him to, and just as God called Israel to leave Egypt behind with its pantheon of false gods, and just as Jesus leaves this world behind in order to go to the Father (Jn 17), so too in matrimony, two people are called to leave behind a world closed in upon itself; they are consecrated, that is, set apart, for they are called to leave behind their comfortable world of independence and self-sufficiency, to be given over to another, to belong completely to one another, in order to become part of something larger than their own individual selves, namely, the one flesh institution that is their marriage. The couple relinquish their individual lives; they are no longer two individuals with their own independent existence; rather, they have become one body, a symbol of the Church, who is one body with Christ the Bridegroom. The lives of a married couple are a witness of the Church’s response to Christ’s love for his Bride; they witness that love in their sacrificial love for one another, and for the children who are the fruit of that marriage–and raising children well demands a tremendously sacrificial love. In giving themselves irrevocably and exclusively to one another, without knowing what lies ahead, a young couple die to their own individual plans, they die to a life directed by their own individual wills. In doing so, they find life; for they have become a larger reality.

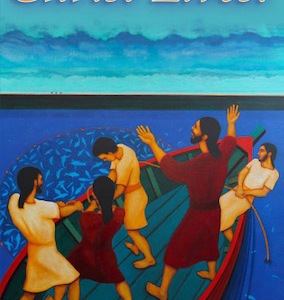

The second point I’d like to make has to do with the Authority of Christ in the gospels: the people were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority and not as the scribes. I am reminded of a former principal of mine. She retired, but she has been called a number of times to take over a few schools when the principal was off for whatever reason. I know the staff morale at one school in particular was quite low, due to a lack of good leadership, which students perceive quite readily. My friend was called to that school to take over for a few weeks. I asked a former colleague at that school: “How did the students receive her?” My colleague replied: “Instant respect”. And this is just what I expected; she walks and talks with authority. But what does that mean exactly? It means she is a person that the students respect, because she is respectable. Just having a position of authority does not mean a person speaks or acts with authority; most people in positions of authority today, including ecclesiastical positions of authority, have very little authority; they’ve lost a great deal of their credibility and moral authority. Authority comes from within; it has to do with the kind of person that you are, and young people can discern rather quickly what kind of person that is. Authority comes from a spirit of charity, holiness, humility, and perfect love casts out all fear, so it involves a spirit of fearlessness, which is very different from a spirit of audacity or boldness. Boldness is rooted in arrogance, in a condescending spirit, but fearlessness is rooted in holiness and charity. The holier a person is, the greater is their authority, and it is an authority that others recognize. And by holy I do not mean sanctimonious. Jesus was the “Holy One of God”, the Scribes and the Pharisees were not holy, which is why they taught without authority. They were sanctimonious, that is, hypocrites, which in Greek means “actor”. For them it was about appearances and having others fawn all over them, lording it over others, but as Christ said, they neglected the poor and the suffering. The demons were terrified of Christ because he came with the authority of God the Son, who humbled himself and came among us, to deliver us from the Satan’s dominion. The more we grow in true holiness, in the power of charity and humility, the more we will be empowered by his authority.