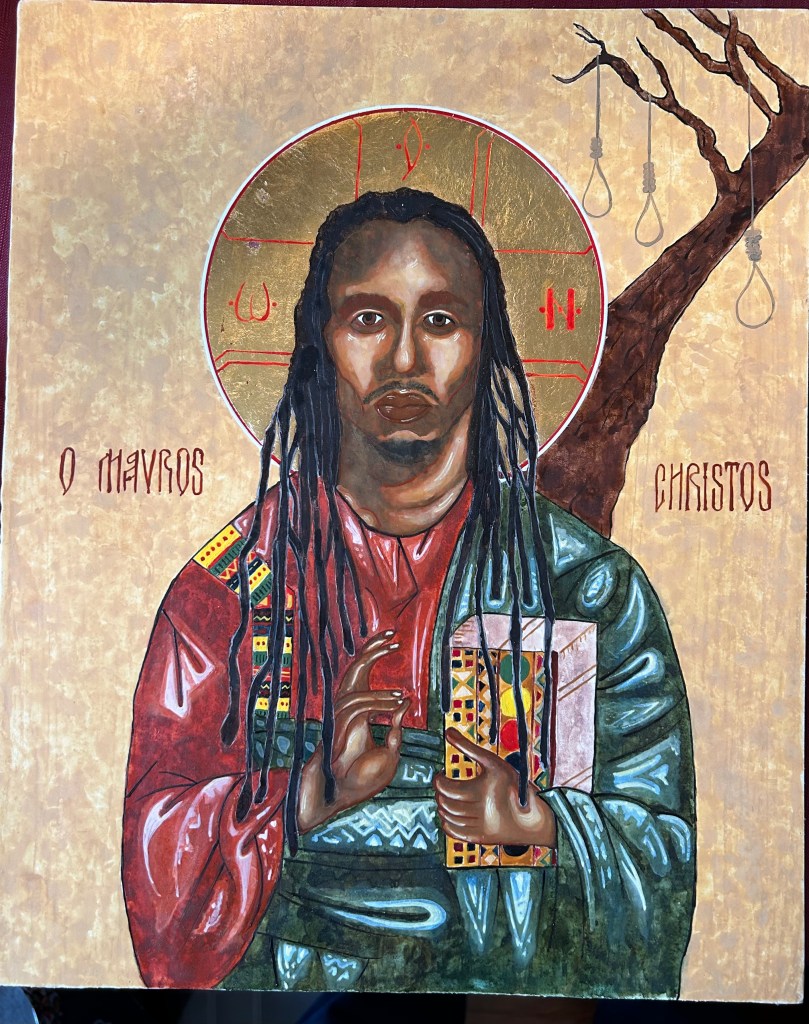

Deacon Doug McManaman

I was inspired to write this Icon (O Mavros Christos/The Black Christ) while reading James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree. It was Rev. David McClearly who, soon after we met at Southlake hospital in Newmarket, ON, suggested I read this book. At the same time I recommended that he read G. Studdert Kennedy, Episcopalian chaplain to the British Army during WWI—specifically his book The Hardest Part. One of Studdert Kennedy’s great poems is entitled Indifference:

When Jesus came to Golgotha, they hanged Him on a tree,

They drove great nails through hands and feet, and made a Calvary;

They crowned Him with a crown of thorns, red were His wounds and deep,

For those were crude and cruel days, and human flesh was cheap.

When Jesus came to Birmingham, they simply passed Him by.

They would not hurt a hair of Him, they only let Him die;

For men had grown more tender, and they would not give Him pain,

They only just passed down the street, and left Him in the rain.

Still Jesus cried, “Forgive them, for they know not what they do,”

And still it rained the winter rain that drenched Him through and through;

The crowds went home and left the streets without a soul to see,

And Jesus crouched against a wall, and cried for Calvary.

This poem prepared me for the impact that James Cone’s book was going to have on me. It was one of the most deeply moving books in theology that I had read up to this point in my life. It left me speechless on a number of occasions. He writes:

The lynching tree is a metaphor for white America’s crucifixion of black people. It is the window that best reveals the religious meaning of the cross in our land. In this sense, black people are Christ figures, not because they wanted to suffer but because they had no choice. Just as Jesus had no choice in his journey to Calvary, so black people had no choice about being lynched. The evil forces of the Roman state and of white supremacy in America willed it. Yet, God took the evil of the cross and the lynching tree and transformed them both into the triumphant beauty of the divine. If America has the courage to confront the great sin and ongoing legacy of white supremacy with repentance and reparation, there is hope “beyond tragedy”.

I’ve studied iconography for many years now, and I knew that I wanted to “write” an icon of a black Christ–after all, Jesus was not white. But most importantly, the fundamental reason I have for this idea is that the moral and spiritual life of a believer is about becoming the unique Christ, which Christ can be in you individually, in me individually. When you are the person Christ intends you to be, when it is no longer you who live, but Christ who lives in you (Gal 2, 20), then Christ appears in this world uniquely, through you. No one can be that unique Christ except you. And when you are that, you have a beauty that no one else can possess. There is a beauty that only you can bring the world. And so there is a “black Christ”, an Asian Christ, an Indigenous Christ, a Caucasian Christ, etc. I also knew I wanted a Christ with dreads. The symbolism of dreadlocks is rich and broad. It symbolizes connection to the divine, resistance against oppression; it is a symbol of African heritage and identity, and it became an emblem of resistance against colonial oppression. Of course, dreadlocks are an ancient symbol of wisdom and spiritual insight. Also, I wanted to make sure to include a “lynching tree” in the background. I cannot explain this better than Cone himself who writes:

As I see it, the lynching tree frees the cross from the false pieties of well-meaning Christians. When we see the crucifixion as a first-century lynching, we are confronted by the reenactment of Christ’s suffering in the blood-soaked history of African Americans. Thus, the lynching tree reveals the true religious meaning of the cross for American Christians today. The cross needs the lynching tree to remind Americans of the reality of suffering–to keep the cross from becoming a symbol of abstract, sentimental piety. …Yet the lynching tree also needs the cross, without which it becomes simply an abomination. It is the cross that points in the direction of hope, the confidence that there is a dimension to life beyond the reach of the oppressor. “Do not fear those who kill the body, and after that can do nothing more (Lk 12, 4).

I would like to emphasize, however, that the tragedy of Good Friday was transformed into the beauty of the divine light, and thus the same is true of the lynching tree. Cone writes:

Though the pain of Jesus’ cross was real, there was also joy and beauty in his cross. This is the great theological paradox that makes the cross impossible to embrace unless one is standing in solidarity with those who are powerless. God’s loving solidarity can transform ugliness–whether Jesus on the cross or a lynched black victim–into beauty, into God’s liberating presence. Through the powerful imagination of faith, we can discover the “terrible beauty” of the cross and the “tragic beauty” of the lynching tree.

The following are pictures of the stages of development that this icon went through. The first stage of the writing of an icon is the preparation of the sketch and transferring it onto the gessoed surface of a poplar wood board. The gold leaf is then applied to the clay surface.

The first layer in the painting process is roskrysh, which is followed by first lines, and then the first highlight. After the first highlight, one applies the first float, which dampens the brightness of the highlight. After the first float, we apply a second highlight, followed by a second float, a third highlight followed by a third float, and finally the second lines. The icon then sits for two weeks to dry before olipha (applying linseed oil).