September 27th, 2024

Deacon Doug McManaman

Whenever I am asked to give a retreat talk to a staff of teachers, I usually have to think hard about it: “Is this something I can do or should do, etc., but when I was asked to give this faith day talk for McGivney, immediately I knew that I wanted to be here for this. There was no need to think about this for more than two seconds. Now, I don’t come to Markham often, but these past few years I have had to drive to 48 and Steeles for some eye appointments, so I would end up driving by the school. And I have to tell you that every time I’ve done so, I was left with a very real and palpable feeling of joy. I find it very interesting to think about this. I experience joy for the rest of the day. It’s an interesting phenomenon, because there is so much that I’ve forgotten, so many details–I spent my last 20 years of teaching here, and memories do fade, especially as we get older, so it’s not as if I have a collection of distinct memories that bring me joy. They are subconscious memories. There was something very beautiful about this school, the students and the staff. A whole world is opened back up to me when I drive by the school. So I am quite convinced that we did something right at this school: the staff did something right, and the students did something right. And I’d like to spend some time reflecting upon just what that might be.

I know the theme of the retreat day is hope, and one of my favorite themes to preach on at Mass is divine providence, precisely because of the hope it provides those who really think about providence, the idea that God is in complete control of all things, that every moment of our existence is within his providential hands. My former students have often told me that one of their best memories from our class is of the day I told them the story of my return to the faith. I was baptized a Catholic and went to Catholic school up until grade 3; after that, I was sent to the “Protestant” school across the street from my house in Dollard des Ormeaux, a suburb of the west Island of Montreal. We then moved to another part of Montreal, and I never went back to a Catholic school again, so I was sort of an atheist by the time I was a teenager. I did not grow up Catholic after that.

My entire life was music. Bluegrass music. I was a five string Bluegrass banjo player, I played in two Bluegrass bands before deciding to go to University. But the turning point in my life came when I decided to hitchhike to Nashville, Tennessee. Clearly I was lacking a prefrontal cortex; I had absolutely no sense of danger when I was 17 years old. Now when I drive to Cincinnati, Ohio, I take 75 south, the route I took when hitchhiking, and even with the doors locked, I still get scared going through Detroit and Columbus, Ohio; how I was able to hitchhike down south with only $150 is beyond me. The only explanation is an undeveloped prefrontal cortex.

But it was the most providential event in my entire life. I got a lift just outside of Columbus from a Catholic priest of the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C, and he drove me all the way to Kentucky. As I got into the car, after putting my backpack and banjo in the back seat, I asked him what he did for a living. He said: “I am a priest”. I thought that was interesting, and of course the last time I saw the inside of a Church was in the 3rd grade, so I used that time to question him, challenge him, question him again: How do you know God exists? Why would you take a vow of celibacy? Why do you need religion in your life, etc.

But what struck me about this priest were two things. First, he related to me as an equal. There was an eye to eye relationship; there was not an ounce of condescension, not even the slightest indication that he was superior in any way. He related to me with a kind of reverence, for lack of a better word. Secondly, his joy. He was clearly happier than I was. He’s in his mid 30s, he’s got all these responsibilities and obligations, he can’t get married, I’m young, free, I can get married, but there’s no doubt in my mind that he’s just happier than I am. And that was a mystery to me. I had a sense that he belonged to a world that I once knew as a child, and I guess I wanted back into that world. I had lost touch with it, and wanted back in. And he revealed that world to me, just by the kind of person that he was: a person of great joy, without any pretensions.

At one point, he asked me if I went to Mass, and of course I said no, and he asked if my parents went to Mass, and I said no, and he was so disappointed. I couldn’t understand it. “Why do you have to go to Mass?” I asked him. “People can pray on their own”. And he yelled out the answer: “To receive the body of Christ”.

Now I hadn’t heard those words in years, since the 3rd grade, and I knew at that moment that this was the key to entering back into that world that I once knew as a child, the world that this priest belonged to, which was a joyful world. So I decided to get back to Mass from that point on. He dropped me off on the side of the road where he had to exit; I played my banjo for him outside, took down his number and address and promised to keep in touch with him.

I made it to Nashville and joined the Rudy Meeks Band. He’s a 6 time Canadian fiddle champion, so I went all the way to Nashville to get a job in a band back in Canada.

And I did keep in touch with that priest, and I did return to my faith as I said I would. What was interesting about the rest of his trip was that when he got to the seminary in Kentucky, there was nothing for him to do. He had to get up the next morning and leave and return to Washington, D.C. there was simply nothing for him to do there. The bishop sent him to visit this seminary, but the trip was a complete waste of time. And after a while, he came to realize that the only purpose to that trip was to pick up a hitchhiker, relate to him as an equal, buy him lunch, answer his questions, and inspire him. The bishop of course didn’t know that. So it was the one time in his life that he felt that God chose him to be at a particular place at a particular time.

After touring with the Rudy Meeks band and another band, I decided to leave the music industry. I wanted to become a priest, which led me to St. Jerome’s College at the University of Waterloo; two years into philosophy, I met a woman, and I thought “Maybe I don’t want to be a priest after all.”

So I studied philosophy at Waterloo and theology at the university of Montreal, went to McGill university for teachers college, and my first 10 years of teaching were in the heart of the Jane and Finch area of Toronto. The school was Regina Pacis, and it was founded by Father Gerald Fitzgerald, of the Holy Ghost Fathers, and he wanted to establish a school for kids in Jane and Finch who could not get accepted into St. Basil’s, which only accepted the best at the time. So he handpicked his staff, those who shared the same vision of education, who were aware that this is not going to be an easy task but who were committed to it, and he made sure we had a first Friday Mass and social every month, with alcohol. And those were great years, but they were rather difficult years. Jane and Finch was and probably still is a very broken neighborhood. I spent my first ten years there. I then spent two and a half years at Chaminade College, an all boys school, and that was a very different experience. The kids were always in uniform, and their attention span was not 7 minutes, as it was in the previous school, but a full hour. It was a very easy place to teach at. But then I soon decided to switch to York Catholic, because of the driving. And my first interview was here, in 2001, with Paul Walsh, Kathleen Westmaas, and Domenic Scuglia.

I didn’t think I was going to remain at McGivney, because I wanted less driving, but I ended up here for the rest of my career. There was only one point where I tried to leave. When St. Maximilian Kolbe opened up in Aurora, I applied for the headship in Religion. Dominic Scuglia wanted me to apply for the headship, I would have been able to walk to work every day, and my friend Eugene Pivato coached me on how to answer the questions that they were going to ask.

But when I sat down for the interview, it was so interesting. My mind went completely blank. I couldn’t answer the questions. I felt like a complete idiot; I was just fumbling all over the place. When I got back to McGivney, I saw Kathleen Westmaas, who was now the principal; she was in the parking lot heading off to a meeting at the board, and she asked me: “How did the interview go?” I said it was terrible; horrible. I couldn’t answer a thing. In her Trinidadian accent, she says to me: “That’s God’s way of telling you to stay with Kathleen. Stay with Kathleen.” And of course, she was right. The headship for religion opened up a week later, and she wanted me to apply for it, so I said I would, but “I’m not giving canned answers. I’m going to answer the way I want and if they don’t like it, too bad. And I’m bringing notes in case I go blank. We make accommodations for our students, so you have to make accommodations for me”. And that interview was a breeze. And after that, they brought in the IB program, which gave me a new lease on teaching for my last 6 years. And so, screwing up that interview for Kolbe was one of the greatest blessings of my teaching career.

Teaching at McGivney was a blessing on so many fronts. One of the things I continue to reflect upon is the ecumenical aspect of this school. Prior to McGivney, it was always only Catholic students that were registered in the schools I taught at. Here, a significant percentage of Muslim students, Hindu students, some Sikh students, Buddhist, atheists, alongside Catholic kids. That was a very important experience. So many people I know, who are serious Catholics, did not have that experience or anything similar, and so when they speak about those who belong to non-Christian religions, especially Muslims, they do so not from any concrete experience, but from what they’ve deduced in their heads, on the basis of their assumptions. And what they say is not always very good, often very ignorant, very much rooted in fear and a kind of religious tribalism, an us-and-them mentality–and these are well educated people I’m referring to.

My best friend is a retired priest from the Hamilton diocese, and one of the last things he did as a pastor in Kitchener, Ontario, was to sponsor a refugee family from Syria, a Muslim family. That family fell in love with my friend, Father Don Sanvido, and to this day they treat him as one of the family. I was there for supper one day, and I saw how much the children of that family loved my friend, the joy of that family, their appreciation for all the parish and this priest in particular did for them. And I asked my friend after we left: “Notice how joyful and charitable that family is. Do you notice any difference between them and Joe’s family?” Joe is a friend of ours, a Catholic teacher with a large family, and visiting them over the years was also a joy. “Do you notice any difference in the way you are treated by Mohammed and his family and the way you are treated by Joe’s family? Any difference in the overall atmosphere?” And he said to me: “No, I don’t notice any difference”. Both homes are filled with the joy of the kingdom of God. That was an important experience for him.

I remember ordering a number of books for our library at McGivney, some Muslim authors, and I was visiting my friend one weekend–I’d often visit him, give him a break and preach for him. At the time I was reading some great Muslim and Sikh religious texts, and so I decided to test my friend, with a bit of deception. I said to him, as a test, to tell me where in the Old Testament can one find the following words:

The One who created the million species of being gives sustenance to all. The Lord is forever merciful; He takes care of all. Those who hear and believe, find the home of the self deep within. Those people, within whose hearts the Lord abides, are radiant and enlightened. Speak of Him continually and remain absorbed in His Love.

He was sure it came from one of the wisdom books, such as Sirach or Ecclesiastes. But this came from the Sikh holy book, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Before telling him that, I asked him to tell me which mystical theologian in Church history would have said the following:

Does anyone think that the ocean is only what appears on its surface? By observing its hue and motion, the keen eye may perceive indications of that ocean’s unfathomable depth. The Lord’s mercy and compassion are an ocean with no shore, providing endlessly varied vistas for those who sail its surface; but the greatest wonderment and fulfillment is reserved for those “creatures of the sea” for whom that mercy has become their own medium.

The Lord beckons us through a divine love and attraction that has been implanted in our hearts, a love that may be understood and felt consciously as divine by some, and only indirectly as love for His creatures or creation by others. In either case the pull of our heart draws us to those Mercy Oceans, just as our physical bodies feel drawn to a warm and gentle sea….we are of that sea, our place, our home is in the depths of that sea, not on its surface.

After I finished reading this, my friend listed the following possibilities: Meister Eckhart, one of the desert fathers, Pseudo-Dionysius, St. Gertrude, St. Hildegard. But no, it came from a modern Sufi writer Shaykh Muhammad Hisham Kibbani–Sufi is the mystical branch of Islam. My friend thought it was from one of the great Catholic mystics. And you know, only prejudice could keep us from recognizing the supernatural quality of these texts.

One of the benefits of retiring is that you have time to explore things that you didn’t really have time for when teaching. And it is amazing how many buried and relatively unknown treasures there are to uncover, especially among non-Catholic thinkers. One great treasure that I stumbled upon was a Chaplain to the British army in World War I, Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, who wrote in the midst of battle, when shells were exploding all around him. Here’s something that Studdert Kennedy wrote in 1920, forty years before Vatican II will begin to move in this direction:

I do not think there is any doubt that we have grossly underrated the moral and spiritual worth of other religions, and have allowed prejudice to blind our eyes to their beauty, and to the foreshadowing of Christ which they contain. It is a tragedy that we should have allowed a spirit of almost savage exclusiveness to have blotted out for us the revelation of God contained in earth’s million myths and legends, so that Christians have regarded them almost as though they were the inventions of the evil one. It is a disaster that we should have lumped all other faiths together and called them “pagan”—dismissing them as worthless. It is disastrous because it has distorted our missionary methods and delayed the development of the world religion. It has made us seek to convert the East not merely to Christ, but to our specifically Western Christ, and to force upon other peoples not merely our experience of Him, but our ways of expressing the experience. It is disastrous, too, because it has bred in us the spirit of intolerance and contempt for others which is one of the chieftest obstacles to the union of the world.

That’s an astounding text, especially in light of the fact that it was written in 1920. There is no doubt in my mind that this text is still ahead of our time–not even Vatican II was that daring. Teaching at McGivney among so many Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims, among others has been a genuine blessing, because we saw how much reverence they have for all that we believe. I recall a Muslim student going through each desk in period 1 in a room I had in that period on the 3rd floor one year, and he was removing the bibles from the desks, and stacking them neatly; he’d do this every morning, for those bibles were left in the desks by students in period 4 the previous day. This Muslim boy would shake his head and say: “Sir, these students have no respect”. And he’d place the bibles on the table at the side of the room.

Now, I’m not at all sure that leaving a bible in a desk is irreverent, but he thought so, because to do that to the Koran would be irreverent, so it was his reverence for our Scriptures that struck me. There are so many instances like these that filled my 20 years at McGivney. I remember grade 12 male students walking into period 1 looking so tired and hungry, because it was Ramadan, and they were determined to observe the fast. And that too challenged me in my final years. As you can see, I don’t have the body of a person who is good at fasting, and our Lenten fast is nothing compared to their Ramadan fast. But in my last few years, I felt guilty for my lack of effort, and so I did make a real attempt to crank it up, as a result of their example. Again, that’s just one among many. And there are the Hindu students with their openness and willingness to learn from everyone. And there’s the irony: the word Catholic is from the Greek kataholos, which means ‘on the whole’ or universal. The Hindu students have that universal openness and willingness to embrace all that is good, a truly Catholic attitude, whereas we Catholics–not you necessarily, but certainly in many parts of the world today–have become so sectarian and tribal, so closed to anything that is foreign. Consider the recent ruckus caused by the Pope’s recent remarks in Singapore regarding the great religions of the world as “paths to God”. It seems we’ve gone backwards, some of us at least.

And those twenty years at McGivney have helped me to understand more deeply Pope John XXIII’s vision of the Church at Vatican II. Many bishops at Vatican II, like the Belgium Bishop Emile-Joseph De Smedt, were breaking away from the image of the Church as a pyramid, with the Pope on the top, bishops and priests below as his intermediaries, and at the bottom of the pyramid was the laity. Such a model tends to regard the Church as primarily and principally clerical. Vatican II moved beyond that model towards a concept of the Church as an Open society–fundamentally, the people of God–a pope, a bishop, a priest, are one of the faithful, like you and me, and they’re called to temporarily serve in a certain capacity. The Church is not the hierarchy, it is much larger than that, and it is much larger than the Roman Church. Hierarchy means ‘sacred order’, not levels of perfection from the inferior to the superior. The movement of the Church is not to be centripetal, but centrifugal, outward, towards the world. In that old pyramid model, the main effort of the Church’s apostolate was to bring the other peoples into the Church. Recruitment. Fill the pews.

In 1959, John XXIII wrote in his diary: “The whole world is my family. This sense of belonging to everyone must give character and vigour to my mind, my heart and my actions. This vision, this feeling of belonging to the whole world, will give a new impulse to my constant and continual daily prayer:…” There’s no doubt that his experience as head of the Vatican diplomatic mission to Turkey was the root of this feeling, which was behind a new model of the church that was developing under his leadership. As Piet Fransen S. J., pointed out, the center of human history is not the Church, but the realization of the kingdom of God in the Person of Christ. The Church does not have a monopoly on salvation. The Church is called to serve all men and women and not merely the baptized. Pope Francis is very familiar with that vision and has been trying very hard to bring the Church back to that model. The day before his papal election, when he was Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, he quoted a passage from the Book of Revelation in which Jesus stands before the door and knocks. He added: “Today Christ is knocking from inside the church and wants to get out.”

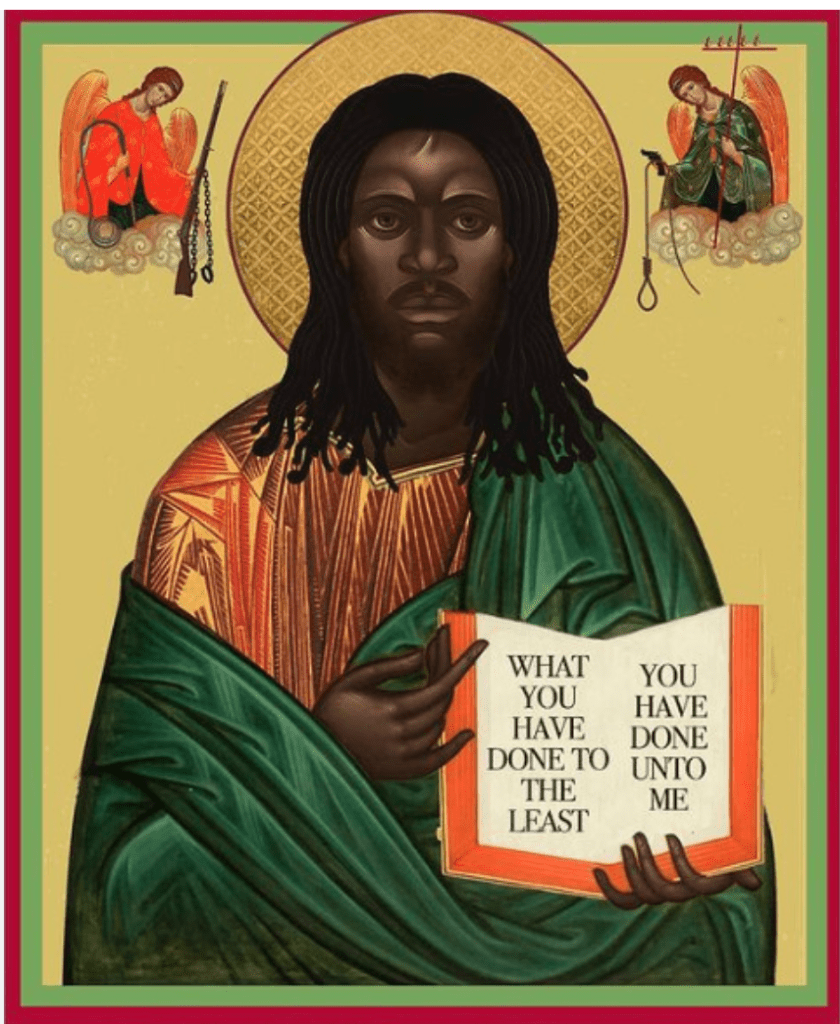

The foundation for this vision is in the Incarnation. The Second Person of the Trinity, God the Son, joined a human nature to himself, and Vatican II points out that in doing so, God the Son joined himself to every human person, not just the baptised. And so, God the Son is intimately present to every man and woman in the deepest regions of the human person; sufficient grace is available to everyone, and every decision we make in our lives can be translated as either a ‘yes’ to God, in which case we move towards Him, or a ‘no’, in which case we move away. Lumen Gentium sections 15 and 16 are very clear that divine grace is available outside the visible boundaries of the Church of Rome, and that outside of those boundaries, whether among our non-Catholic brethren (Lutherans, Anglicans, Mennonites, Presbyterians, etc.), or non-Christian brethren in the religions of the world, and even among atheists, people can and do respond to the impetus of divine grace in a way that directs their lives fundamentally to God, and grace of course is the indwelling of the Holy Trinity. And so we can really say, as Kathleen Westmaas would always remind us, that this person here, this Hindu or Sikh or Muslim, is my brother, my sister, and that this is what we want our students to understand by lived experience, and those students who do understand this help us understand this more deeply. The wonderful thing about this school is that many of the non-Christian kids, after a time, came to the realization that this Hindu person who has been sitting next to me in math class for the past two years or so, or this Catholic, or this Sikh, is not the infidel that I might have been led to believe he or she was. And vice versa.

And any Catholic teacher who doubts this, who still operates out of a kind of tribal Catholicism, has to just consider the fact that if you believe what St. Paul teaches in his letter to the Galatians, that “it is no longer I who live but Christ who lives in me”, then in loving you and what you stand for, your students really love Christ without necessarily knowing it explicitly. That Muslim family from Syria that my friend sponsored, through the parish, that family, in loving my priest friend and receiving him into their home as their uncle, they are loving Christ without them necessarily realizing it or knowing it explicitly–because that’s all he has in his life, that’s his whole identity and all he lives for.

That’s evangelization, that’s proclaiming the good news of Christ’s resurrection, and that’s very different from proselytizing. So many Catholics today still confuse evangelization with proselytizing, with recruitment. Evangelization is witnessing to the good news that Christ is risen, that our greatest fear and the one enemy that man was helpless to defeat, has been defeated by Christ: namely death: “By dying you destroyed our death, by rising you restored our life”. And we proclaim that good news by carrying that risen life within us, by living in the joy of Easter. That’s what did it for me when I was 17 years old and hitchhiking; it wasn’t the answers to my questions that I was given by this priest, nor any kind of apologetics that brought me back. It was his joy and the eye to eye relationship he was able to establish. And that’s how we evangelize our students, by entering into their sufferings, paying attention to them, and joining our light to their darkness.

And I know that over the years, a number of Muslim parents would express to me their fears, on grade 8 Curriculum night, fears that we are going to convert their child, recruit their child to the Catholic faith. And unfortunately, we only see in others what we see in ourselves, and a large percentage of devotees in the world religions also think in terms of a closed society, that you really have to belong to “our group” if you are to be considered genuinely religious and pleasing to God. But that’s not what this school was about at all, and Muslim and Hindu parents, many of them, came to see that over the years. What impact that had on their own religious attitudes is uncertain; whether that helped any of them escape their own religious tribalism, we can only hope. But there is no doubt in my mind that the kingdom of God is among you, as Christ tells us in the gospel of Luke, and the kingdom he established is a universal covenant, an international covenant (kataholos), not a tribal family covenant, and the wonderful thing about the Church is that it is in continual reform. The Church, by its very nature, cannot remain static, although many individual Catholics are determined to keep it static, not to move and who believe the Church need not reform in any way. But the Church as a whole is always in reform–which necessarily implies that the history of the Church is rarely ever pretty. At every moment of its history, it is always a Church in need of reform.

But this is true on an individual level as well. That’s so important to recognize. Each one of us is always in need of reform. I don’t know about you, but I don’t like seeing myself in the past, either on an old VHS cassette or in old photos that remind me how stupid I was at that time. I often shake my head, saying to myself: “I can’t believe I said that to him”, or “What an idiot I was for doing that”, etc. And this is one of the best things about retirement. Two other friends of mine retired shortly after I did, and what all three of us have in common is we’ve spent the last 5 years or so reflecting on our own lives, looking back and seeing that if we had to do certain things over again, we’d do many things differently. In other words, we do regret some of the attitudes we had at one time in our lives.

Teaching theory of knowledge made this process a bit easier. To prepare students for writing their TOK essay, I decided to study the philosophy of Nicholas Rescher, from the University of Pittsburgh, one of the greatest philosophers of science in the 20th century. And I wanted to find a way to make his thought easy and accessible to the IB students, so I studied his theory of plausible reasoning. To make a long story short, let’s just say that knowledge is very hard to achieve, and much of what is in our heads is not knowledge at all, but belief (natural faith), some of it warranted, much of it unwarranted. And so Rescher was a real proponent of epistemic humility and the importance of coming to a deeper awareness of the limits of human knowing, that it is not so much truth that we possess, as it is truth as I currently see it. He does not deny the possibility of possessing truth, but he argues that it is much more difficult than most people are willing to admit.

So I got in the habit of paying very close attention to the inferences that I would make on a daily basis, particularly the mistaken inferences, and I would use those as examples in my theory of knowledge classroom. It’s hard to get adolescents to appreciate the limitations of human knowing and the tentative nature of our truth claims–we tend to be rather doctrinaire when we are young and speak with a rhetoric of absolute certainty, so I needed lots of examples for them. After a time, you get used to the fact that we are quite often wrong. But it is especially interesting discovering, in your 50s and 60s, that certain beliefs you’ve held onto for decades might not be as sure and definitive as you once thought. When I was in my 30s, things were different; 30s is young, so too 40s, so being wrong is something that doesn’t stand out that much; on the contrary, when we are young, it’s being right that tends to stand out, and it’s a good feeling being right. But when I turned 50, things changed, because I saw 50s as ‘getting up there’. Thomas More, one of my favourite saints, was executed outside the Tower of London when he was 57; I always wondered what it would be like to be in my 50s, which I saw as ‘old’. So, when I turned 50, 51, 52 etc, and I discovered that so and so was right after all, 20 years ago when he said that and when I argued against him so passionately, that had a different impact on me. I couldn’t hide from it. I would say to myself: “It took me 20 years to figure that out”, or “30 years to discover that so and so was right after all”, or “I’m 56 and I’m just learning that now”? Why did it take so long? and things like that are still happening. I’m 63 now, and I’ll be reading something written in 1885, by an unknown Protestant theologian, at least unknown to me for the past 60 years, and I’d think to myself: “This guy knew things about scripture and the Church fathers, and the nature of God, back in 1885, which I’m only learning today, through him, in 2022 or 23–and what he’s saying is still very much ahead of our time. It’s a fascinating experience. And I really do feel like a beginner all over again. It sounds counterintuitive, but it is an exhilarating experience to discover that “I’m far more ignorant than I realized”, and that there’s a brand new path to explore for the next few years. It reminds me of Physicist Richard Feymann who said that science is an ever expanding frontier of ignorance. The more we discover, the more we come to know how much more there is to know, and how much we didn’t know, but thought we knew.

And my two best friends are experiencing much the same thing. And I think that might be the key to longevity. When you feel like a beginner all over again, you feel young again, at the start of a new adventure. And that spawns hope. A continuous cycle of new hope. You kind of have something to live for again, something to achieve, something to master, and that may take 2 or 3 years, then it happens again. So life really is a learning process. And that’s what makes teaching so much fun. You learn new stuff, and try it out on the students, see what they think.

Teaching is a very noble profession. The work is holy. When we enter a classroom, we are walking on holy ground, as God said to Moses when he approached Mount Sinai. But teaching is a way of the cross, and that’s the beauty of it. We have a tendency to assume that life is not meant to be a struggle, that when things are difficult, something is wrong. A friend of mine, a principal from years ago in the Toronto board, would always identify a good say with a smooth day, and I used to challenge him on this: “A smooth day is not necessarily a good day, and a day with all sorts of headaches, frustrations, difficulties, and stress, might very well be the best day of the week, the most fruitful and effective.” He was a friend of mine so he could talk to me in a way that he would not talk to others, which is why his reply consisted of two words that I cannot repeat here. But as anyone who has studied evolutionary biology well knows, life itself is a struggle. It’s supposed to be. Marriage is a struggle; teaching is a struggle, working with young people is a struggle, working with administrators is a struggle, and vice versa. But the Second Person of the Trinity joined a human nature to himself in order to enter into that struggle and conquer it, to become victorious over it in a way that we could not; and that’s the mystery of his cross and resurrection, and our greatest gift is to be given a share in his cross and resurrection, that victory over the struggle of human existence. In the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus’ prayer was not “Let this cup pass from me”; that was a moment of weakness in the Son of God, interestingly enough. His prayer was “but let not my will be done, but Your will be done”. Studdert Kennedy points out that this is the real prayer of Gethsemane: “This prayer is immediately answered. The angel of God appears to comfort Him. Terror dies within his soul, hesitation disappears, and with His battle prayer upon His lips, ‘Thy will be done,’ he goes out from the garden in the majesty of manhood to bear such witness to His truth, to live in death so fine a life, that He becomes the light in darkness of every age, and the deathless hope of a dying world.”

God the Son entered into human suffering in order that we may find him there, and be given the divine life, the grace, the strength, to heroically endure. And of course he gives us his very self, his body, blood, soul and divinity under the ordinary, mundane appearance of a wafer of bread. The Eucharist is our strength, and I have to say that the greatest gift I’ve been given in my entire 32 and a half years of teaching high school was that in every school I was at, there was a school chapel with the blessed sacrament. To be able to visit first thing in the morning, and to drop by for 30 seconds many times during the day and finally at the end of the day, was easily the source of strength that kept me from burnout and despair.

The bitterness of the cross always ripens into a profound sweetness, because charity is sweet, and teaching is a work of charity, and the joy of heaven is an unimaginable sweetness and ecstasy that does not end. My spiritual director always quotes St. Augustine who said that God loves each one of us as if there is only one of us, as if you are the only being that exists to love. Each one of us has God’s undivided attention at every instant of the day. God can give us each that undivided attention because he is unlimited. No human being can come close to that–we’re too limited. But to discover that you are loved like that is to discover joy, and then life in the classroom becomes very different than what it was, because we bring that joy into the classroom every day with us, and when that happens, we will give our students a network of subconscious memories that will stay with them for the rest of their lives.

I think Father Michael McGivney is really a microcosmic symbol of hope, hope for a united humanity, a universal fraternity. It’s a microcosmic instance of what this world can look like and should look like and probably will look like in the future–the very distant future, given the lessons that human beings still have yet to learn. And I believe this vision of a united fraternity is at the root of Pope John XXIII’s vision of the Church in the modern world, not a closed society rooted in fear with culture warriors in defensive posture at every corner, but an Open Church, open to the world, open to dialogue with the world, and open to change and reform. This is a vision that Pope Francis understands well.